Below are links to the other posts in this series. Scroll past them to read the article.

- Atomisation

- Overtisation

- Expansion and Context Shaping

- Cognitive load

- Review

- Lesson structure and schemes of work

- Speed principle

- Difficulty and Motivation

- Defining range/scope

- Categories for different types of knowledge

- Instruction for basic types of knowledge

- Instruction for linked types of knowledge

- Instruction for routines

- Instruction for problem solving techniques

- "Real world" maths

- Prompts and scaffolding

- Correcting mistakes

- My take on the strengths and weaknesses of Direct Instruction

Difficulty and Success

Ensuring success, in the acquisition of both individual components of knowledge and whole schemes of work, is at the heart of Direct Instruction. Every part of it was built and tested with this single criteria. Each activity in a DI program is tested and improved until it achieves over 90% success rate of all questions along all students. Even when doing remedial work to correct mistakes and learned misconceptions, DI takes great pains to ensure that students will successfully answer at least 2/3 of questions directed at them (more on this in the correcting mistakes section).

When I am planning a lesson now, I use the following rubric:

- For an initial instruction activity, can I explain this in <1 minute of teacher direction so that >90% of success will be able to perform the task first time, without additional support?

- If not, I need to atomise this further in to components that fit this criteria.

- For review activities, am I confidant that students will remember this topic?

- If not, I need a prompting activity before the review (to be faded in a subsequent lesson).

Motivation

Direct Instruction does not have much to say about student motivation.This, in my view, is one of its main shortfalls, as we all know how much of a factor student motivation is for successful learning. However, it is highly focused on achieving student success. This successful progress is a big factor in most of the popular current theories on motivation. I will demonstrate this below by looking at three theories in particular: the Expectancy-Value Theory, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, and Dweck's Growth-Mindset Theory.

Expectancy-Value Theory

According to this theory, a student's motivation is determined by:

- How much they value the goal(s) that are set

- To what extent they expect to succeed at these goals

These factors are said to multiply, so that if either value is zero (or very low), the overall motivation is zero:

=

=  X

X

Expectancy is obviously heavily tied to your previous experiences of success and failure in that subject. Therefore if, as with the DI model, you are regularly and reliably making successful progress from lesson to lesson, your expectancy of success in future lessons will increase.

DI does not say anything about Value, and so other techniques should be added to a DI program in order to increase this. At some point I plan on making a blog post specifically about this.

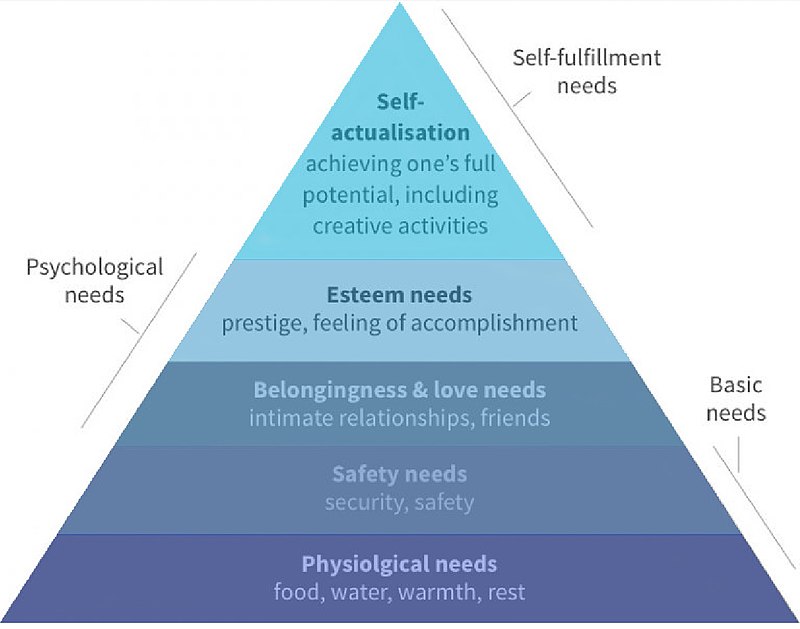

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

The crux of this theory is that individuals’ most basic needs must be met before they become motivated to achieve higher level needs. I feel like this plays right to the biggest strength of DI. This is because, whilst enquiry-based learning, project-based learning, collaborative problem solving, open-ended, rich tasks, etc. all attempt to service a student's need for self-actualisation in one way or another, DI is an attempt to service the deeper, psychological need to build self-esteem. In my experience, it does this very successfully with a wide range of students.

Dweck's Growth-Mindset Model

This model states that some people believe their success is based on innate ability (with a fixed mindset) while others believe their success is based on hard work, learning, training and doggedness (with a growth mindset). This theory has been met with serious criticism and I only include it here because of its popularity within the profession.

A student's beliefs about what causes learning is formed by their experiences of their own and other's successful learning. In DI, a student gets to experience rapid and reliably successful learning. The learning even feels easy for them (so long as they follow along with each section). This means that students get to regularly experience the positive effect of practice on their abilities. This experience can be signposted to make sure that they appreciate it using several techniques:

- Teacher praise

- Pre and post-learning check-in tests*

- Assessment score tracking for students

- Dan Meyer's headache-aspirin set-up to learning*

*these are not included directly in DI, but I have found adding them useful

Addressing concerns

How does this fit with the theory of desirable difficulty?

- Individual tasks are designed to be (or seem to be) easy in all stages

- Feedback is designed to always be instant (or as close as possible to this) whereas some studies have shown that delayed feedback is preferable in certain situations.

- Differentiation is only present in DI in the section under 'correcting mistakes'

However, there are also many ways in which DI fits nicely with the theory of desirable difficulty:

- Spaced retrieval practice/Interleaving: This is at the heart of every DI session (85% of each lesson spend on review)

- The scheme of work remains unchanged; students still learn topics to the same level of difficulty as before - DI just gives a different approach on how to lead up to that level of difficulty.

To account for these discrepancies I have adjusted somewhat:

- I usually do not add any differentiation to initial instruction (as I do want all students to be successful at understanding the central concept). However I do differentiate the expansion and context-shaping activities, as some learners will immediately see wider generalisations and range of applications than others. During these activities I will plan a range of difficulties that students can choose or be directed to.

- For homework (not mentioned in DI) - it is important that it is accessible for all without additional support (it otherwise risks widening the achievement gap). The only way to do this and achieve desirable difficulty is with differentiation. This can be achieved by choice of task or the amount of scaffolding/prompting on the sheet.

- I also try to give feedback instantly during initial instruction (as stated in DI, this is a particularly important time to make sure that students are not learning mis-rules) but will often use delayed feedback for other activities. I still find it difficult to know when to use different types of feedback, but here is a decision tree by improvingteaching.co.uk that aims to help:

No comments:

Post a Comment